Pig Kidney Survives 61 Days in Human Recipient After Rejection Blocked

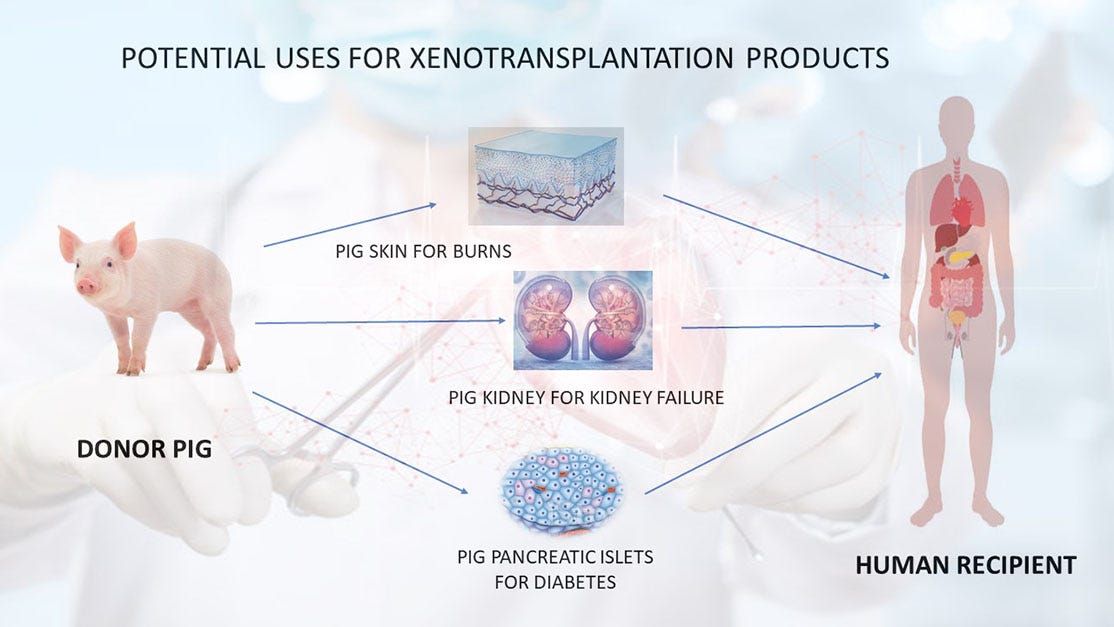

New studies reveal how to stop immune attacks on transplanted pig organs — and hint at applications for living patients.

Scientists have reported the longest-known survival of a genetically modified pig kidney in a human — 61 days in a brain-dead 57-year-old man in the United States. The success, described in two coordinated Nature papers, offers the clearest evidence so far that immune rejection of pig organs can be reversed and controlled. The findings could help advanc…